|

Claustula fischeri Claustula fischeri

BiostatusPresent in region - Indigenous. Non endemic

Images (click to enlarge)

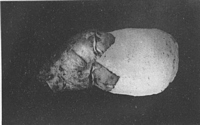

Caption: Fig. 1. Claustula Fischeri, surface view. x 1 1/2. Photograph by W. C. Davies. |

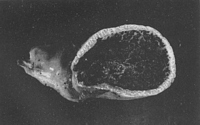

Caption: Fig. 2. Claustula Fischeri, in longitudinal section, x 1 1/2. Photograph by W. C.

Davies. |

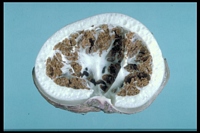

Caption: TEXT-FIGS. 1-6. 1. Volva, transverse section showing pellicle and mucilaginous layers. x

440. 2. Receptaculum, transverse section. x 1 1/2. 3. Mesh of receptaculum. x 440. 4.

Hymenial chambers on inner surface of receptaculum. x 440. 5. Surface view |

Owner: R.E. Beever |

Owner: R.E. Beever |

Owner: R.E. Beever |

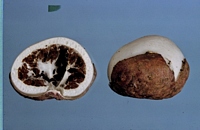

Caption: REB 572

Owner: Ross Beever |

Article: Curtis, K.M. (1926). The morphology of Claustula fischeri, gen. et sp. nov. A new genus of phalloid affinity. Annals of Botany 40: 471-477 London:.

Description: The fungus consists of a volva and a globose to ovate receptaculum. When mature the

receptaculum partially emerges from the enclosing volva, but its lower half remains

loosely held within the latter by the lobes into which it has split (Pl. XV, Fig. 1). In the

largest specimen found, in which the receptaculum was in its final position, the length

from the free end of the receptaculum to the base of the volva was 22 in., while the width

of the receptaculum was 2 in. The volva is ovate before rupture, fleshy-firm in texture,

and when undisturbed in the soil is white, but on exposure to the air becomes a reddish

brown. When mature it ruptures into usually five pointed segments whose length is 1/3 to

1/2 that of the whole volva. The segments do not become reflexed, but tend to lie in the

position they occupied before cleavage, with the result that they rest lightly upon the

receptaculum from its equatorial region downwards, and so prevent it from emerging

completely. The volva is composed of two layers, the outer of which is a firm, thin, finally

coloured pellicle, while the inner is a wider, gelatinous, white layer, slippery to the touch, and

thin above where the segments are formed, but gradually increasing in thickness in the

equatorial and basal regions, where a width of 1-5 to 2 mm. is attained (P1. XV, Fig. 2). The

volva narrows at the extreme base and through it at this point there passes up from the

exterior a slender, fibrous strand about 2-5 mm. wide and 7 mm. high. The upper end of this

strand is attached to the base of the receptaculum and the lower end is doubtless

continued into a rhizomorph, although this was not secured with the specimens. As the

receptaculum enlarges at maturity and is forced up the volva by the swelling of the

gelatinous inner layer of the latter, it breaks away from this strand and thenceforth has a

small hole at its base where the strand was originally attached. The strand, though small,

remains visible even in old specimens and can be seen transversing and projecting a few

millimetres within the gelatinous layer of the volva.

The receptaculum is simply a smooth white shell with a large central cavity. As already

mentioned, it may be z in. across, and as the wall is only from 5 to 8 mm. thick, the

diameter of the central cavity is rela tively enormous. The structure of the wall is

noteworthy. It consists entirely of meshwork, the strands of which are delicate except

where several join, and the rounded cavities of which, though ranging in size, are usually

large, often attaining a diameter of more than a millimeter (Text-fig. 4).

The hymenium is arranged in a layer of small chambers extending over the inner surface

of the receptaculum, and therefore in contact with the cavity of the interior. When mature

the walls of the hymenial chambers rupture, and the spores and the disintegrating

hymenial and subhymenial tissues together form an intermittent and at times jagged layer

over the inner surface of the receptaculum (Text-fig. 4).

MORPHOLOGY.

Volva. The outer surface of the pellicle consists of a dense aggregation of hyphae which

in the unexposed volva when buried in the soil are hyaline, but which become a light

brown, when viewed in section, when the volva has been exposed to the air. These

hyphae are sparingly septate and branch infrequently at a wide angle. The width of the

branch-hyphae is almost equal to that of the parent hyphae from which they arise. They

are about 2 µ wide and the greater part of this width is occupied by the lumen. The free

ends of the hyphae are sometimes irregularly upturned, causing a minute roughness on

the surface of the volva. Such colour as is present is confined to the hyphae at the

surface, those below being hyaline. The sub-epidermal hyphae, although belonging to the

pellicle, exhibit transitional stages not only in loss of colour but in the change from the

parallel arrangement characteristic of the surface layers to the loose weft which occurs

throughout the inner gelatinous layer. In addition, branching becomes less frequent in the

inner part of the pellicle, and the width of the hyphae is reduced, until finally it is no

greater than that of the extremely slender hyphae characteristic of the gelatinous layer. In

the latter region they are rarely branched and are distributed throughout the gelatinous

matrix seemingly indiscriminately as far as direction is concerned; but evenly and

sparsely with regard to one another (Text-fig. 3). There is no differentiation into a

membrane on the inner surface of the volva, matrix and hyphae merely ending abruptly in

a smooth, slippery surface, the hyphae of which show no closer aggregation than is to be

found deeper in the layer.

Receptaculum. The wall of the receptaculum is usually three to four chambers wide, but

if the latter are small they are correspondingly more numerous (Text-fig. 4). The outline

of the chambers is spherical, oval, or even angular, but with the angles rounded, never

sharp. The mesh of the wall consists of extremely thin-walled, usually spherical cells

which are peculiarly uniform in size. The strand at its narrowest part, i. e. where it lies

between two cavities, is three cells wide as a rule, but it is not unusual for there to be

only two cells, and on rare occasions single-celled strands have been observed. At the

junction of several strands, on the other hand, the number of cells is increased and may be

as many as twenty (Text-fig. 5). No thickening of the cell-walls, nor closer aggregation,

occurs at either surface of the receptaculum, all cells alike, from one surface to the other,

being characterized by extreme delicacy, uniformity of size, and high water-content.

The hymenial cavities are more or less lenticular in shape and are arranged edge to edge

with their longer axis in the plane of the surface of the receptaculum (Text-fig. 4). There

is at times only a single row of sterile cells separating the hymenial chambers, but the

width of this intervening tissue is not uniform and it may even exceed that of the

chambers. The width of the chambers varies from 100 to 250 µ, while the height is not

usually greater than 100 µ.. Even the smallest chambers seldom contain less than 100

spores and in the larger the number is nearer 1,000. The spores are borne over the whole

surface of the chamber-on the inner surface of the covering wall as well as on the surface

adjoining the receptaculum. Fragments of the wall covering the chambers were secured,

and sections and surface views of them obtained (Text-fig. 5). The cells of these walls are

angulled rather than rounded, and smaller than those of the receptaculum generally. The

wall in this part seems not to have been more than three cells wide and in some instances

was only that of a single cell (i. e. in addition to the hymenium and subhymenium).

All the specimens obtained were mature, and basidia were no longer to be found.

Moreover, internal decay sets in early in these fruit-bodies, and the structure of even the

subhymenium could not be followed in any of the specimens. The conjugate nature of the

nuclei, however, is still evident even in cells which have collapsed. The spores are brown

in the mass but yellow with a slight fuliginous tone in transmitted light. In shape they are

elliptical to rounded-elliptical, and are either symmetrical or have one side less curved

than the other. As a rule, however, they are symmetrical and vary in size from 8 µ

to 13 µ, x 5 µ. to 6 µ. (Text-fig. 6). Both ends are rounded, but the free end may be

slightly narrower than the base. The wall is smooth and the contents are clear, while the

protoplasm is slight and the vacuoles relatively large. The spore is binucleate, the two

nuclei lying as a rule side by side in. a small cytoplasmic aggregation suspended in the

centre of the spore by extremely delicate strands. It frequently happens that both nuclei

lie in the plane of the longer axis of the spore, but this is not invariable. The only

remarkable feature that the spores exhibit is the presence at their lower end of a

persistent, stout, hyaline, obconic papilla (sterigma). This papilla is about 1.5 µlong

and 0.75 µ wide at its widest part, which is at its point of attachment to the spore.

Habitat: The specimens were growing at a height of 1,500 ft. above sea-level, near the edge of a

path, among moss and practically under tea tree (Leptospermum scoparium, Forst.).

Notes: The fungus is either an unusual member of the Phallineae or has affinities with

that group. In the absence of material sufficiently young to trace its early

development, its systematic position cannot be fully determined It shows greatest

resemblances in form to those members of the genus Clathrus, segregated by Lloyd

as Laternea, in which the divisions of the receptaculum are few in number and

united at their apex. But so far there is no recorded case in which a species of

Clathrus has failed to exhibit any divisions. Moreover, the cellular structure of the

receptaculum of Claustula resembles that of the stalk of certain species of Simblum,

Anthurus, Colus, Aseroi, and Phallus, in which the cells form a pseudoparenchyma,

rather than that of the receptaculum of Clathrus, where the cells on the whole are

tubular. If one could conceive a Simblum or a Colus, or even an Aseroe, in which

the gleba is located within the hollow stem instead of at the top of it, and

developed generally over the interior instead of being confined to definite areas,

and which, moreover, either has not yet evolved or possibly has lost the power of

developing any of the various methods of exposing the spores characteristic of

these genera; then the organism so conceived would not be unlike that at present

under discussion. Both Anthurus and Colus include species, with few arms in the

receptaculum, in which variation in the number of the arms is common. A form

lacking arms would therefore not greatly differ from some of the simpler types of

these genera already known.

Again, the genus Sphaerobolus exhibits some resemblance to the present genus.

The receptaculum is more complex, being composed of three layers instead of one

as in Claustula, but of these three layers the outer and part at least of the inner are

similar in their pseudoparenchymatous nature to the receptaculum of Claustula.

The gleba of Sphaerobolus, on the other hand, fills the space within the

receptaculum instead of lining its inner surface.. Nevertheless, there is a certain

resemblance in the grosser features of the two genera. The spores, moreover, are

more clearly of the shape and size of those of Sphaerobolus than of the small

spores characteristic of the Phallineae. A further characteristic in which Claustula

differs from members of the Phallineae is in the absence of gluten from the

spores, for in the present genus they are only slightly viscid to the touch.

In the absence of details of the early development of Claustula speculation as to its

relationships with other genera must necessarily be hazardous, and it is therefore

hoped that early stages will be found, so that its systematic position may be

established.

Article: Cunningham, G.H. (1931). The Gasteromycetes of Australasia. XI. The Phallales, part II. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 56(3): 182-200.

Description: Peridium obovate, to 4.5 cm. diameter, furfuraceous, white, becoming reddish-brown,

rupturing from the apex to form 4-5 acuminate lobes. Receptacle obovate or subglobose, to 5

cm. long, white, smooth, indehiscent, free within the volva; wall chambered. Gleba borne on

the inner wall of the receptacle, inodorous, non-mucilaginous. Spores olivaceous, elliptical,

smooth, 8-13 x 5-6 µ, shortly pedicellate.

Distribution: Distribution.-New Zealand. Type locality.-Fringe Hill, Nelson, N.Z.

Notes: This interesting plant may be best likened to an egg (the receptacle) held in an egg cup (the

volva). The volva is of the typical Phalloid type, with an outer furfuraceous and an inner thick

and gelatinous layer; but differs in that the third layer is wanting, the gelatinous layer ending

abruptly in a smooth surface. The receptacle is egg-shaped, hollow, of the usual chambered

pseudoparenchyma, and apparently indehiscent. The gleba is produced within a single layer

of lenticular cells, attached to the inner wall of the receptacle. It differs from that of the

typical Phalloids in being practically non-mucilaginous and inodorous. The spores, too, are

much larger than is usual in this order, and are provided with a short persistent pedicel. One

additional interesting feature is that in the immature plant a thin strand of primordial tissue

connects the base of the peridium with the inner tissue of the receptacle through a narrow

pore at the base of the latter.

The absence of peridial plates in the gelatinous layer of the peridium shows that the affinities

of this plant are more with the Phallaceae than the Clathraceae; but the development of the

gleba interiorly to the tissue of the receptacle shows relationships with the Clathraceae.

|